Techniques to Identify Reset Metastability Due to Soft Resets

Modern SoCs are equipped with complex reset architectures to meet the requirements of high-speed interfaces with increased functionality. In this paper, we present a systematic methodology, as a part of static analysis, to intelligently identify critical reset-domain bugs associated with soft resets. A soft reset is a mechanism that initiates a controlled reset within the system without fully powering it off.

-

Introduction

Modern SoCs are equipped with complex reset architectures to meet the requirements of high-speed interfaces with increased functionality. These complex reset architectures with multiple reset-domains, ensure functional recovery from hardware failures and unexpected electronic faults. But the transmission of data across sequential elements that are reset by different asynchronous and soft reset-domains can cause reset-domain crossing (RDC) paths, which can lead to metastability. This metastability can cause unpredictable values to be propagated to down-stream logic and prevent a design from functioning normally. A proper reset-domain crossing sign-off methodology is required to avoid metastability and other functional problems in chip designs.

Introduction

In recent years, the complexity of designs is increasing, resulting in a huge rise in electronic components like processors, power management blocks, and DSP cores. To meet low-power and high-performance requirements, system on chip

(SoC) designs have been equipped with several asynchronous and soft reset signals. These reset signals in the design, help to safeguard software and hardware functional safety as they can be asserted to speedily recover the system onboard to an initial state and clear any pending errors or events.However, with multiple asynchronous reset sources in a design, arises multiple reset-domain crossings (RDC) paths, that can lead to systematic faults and hence cause data-corruption, glitches, metastability or functional failures. These issues are not covered by standard, static verification methods such as clock-domain crossing (CDC) analysis. Therefore, a proper reset-domain crossing verification methodology is required to prevent errors in the reset design during the RTL verification stage. By definition, a reset-domain crossing occurs when a path’s transmitting flop has an asynchronous reset, and the receiving flop has a different asynchronous reset than the transmitting flop or has no reset.

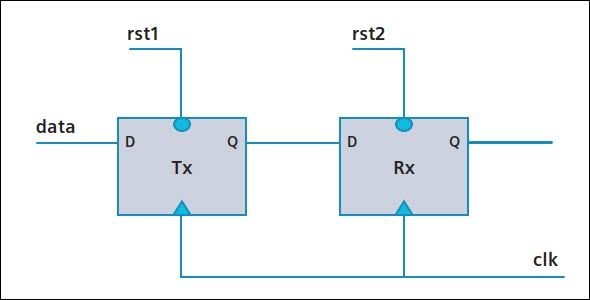

Figure 1a illustrates the simple RDC problem between two flops having different asynchronous reset-domains. The asynchronous assertion of the rst1 signal immediately changes the output of Tx flop to its assertion value. Since the assertion is asynchronous to clock clk, the output of Tx flop can change near the active clock edge of Rx flop, which can violate the set-up hold timing constraints for flop Rx and, therefore, Rx flop can go into a metastable state. Metastability is referred to as a state in which the output of a register is unpredictable or is in a quasi-stable state.

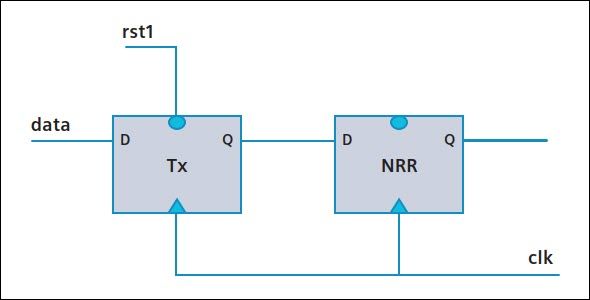

Figure 1b illustrates the RDC problem from a flop with asynchronous reset-domain to non-resettable register (NRR), which be definition does not have a reset pin. An RDC path with different reset=domains on the transmitter and receiver does not conclude that the path is unsafe, and similarly, a RDC path having same asynchronous reset-domains on the transmitter and receiver does not necessarily imply that it is a safe path as the issue may occur due to soft resets (an RDC path through the transmitter to the receiver register in

which metastability can propagate is termed an unsafe path, on the other hand, when there is no metastability propagating in the path, it is deemed to be safe). The different soft resets in a design can induce metastability in designs and hence cause unpredictable reset operations or, in the worst case, overheating of the device during reset assertion.

Figure 1a. RDC between Tx flop and Rx flop from asynchronous reset rst1 to asynchronous reset rst2

Figure 1b. RDC between Tx flop and NRR flop from asynchronous reset rst1 to non-resettable register

-

Download Paper